Cyberspace Cannot Replace Sacred Space

The modern world of electronic communications has, in effect, disembodied us. Many of us spend a great deal of time living neither in a culture nor in a civilization, but in that amorphous region of cyberspace called the World Wide Web.

Cyberspace Cannot Replace Sacred Space

Gabriel Marcel (1889-1973) once described his philosophy as “a persistent, unceasing fight against the spirit of abstraction.” A Catholic convert, Marcel gave a central place in his philosophy to the notion that man is an incarnate being (être incarné).

Human beings do not have bodies; they are their bodies!

“Incarnation is the central ‘given’ of metaphysics”, he proclaimed in ‘Being and Having’.

The modern world of electronic communications has, in effect, disembodied us. Many of us spend a great deal of time living neither in a culture nor in a civilization, but in that amorphous region of cyberspace called the World Wide Web.

There are no bodies in cyberspace and as a consequence, people are not present to each other as fully real, bodified persons. There is no meeting of persons in cyberspace.

We cease to be citizens as we are metamorphosed into netizens—ghostly occupants of the net.

In the web, there is no intersubjectivity, no meeting between the I and the Thou, merely the mingling of discarnate images.

We attain the World Wide Web through processes of dis-incarnation:

from landscape to netscape,

from outerspace to cyberspace,

from text to hypertext,

from etiquette to netiquette,

from ethics to nEthics,

from actual to virtual,

from citizens to netizens.

We suddenly discover that we are, to borrow the title of Gene Rochlin’s book, ‘Trapped in the Net’. We may be developing a new variant of arachnophobia - fear of the World Wide Web.

Catholicism has always celebrated the tangible, and encouraged the tactile.

The Mass and the Sacraments centre on such concrete realities as blood, body, wine, bread, water, candle-lights, altars, statues, eyes, and hands.

It teaches that marriage is consummated only when physical intimacy has been accomplished.

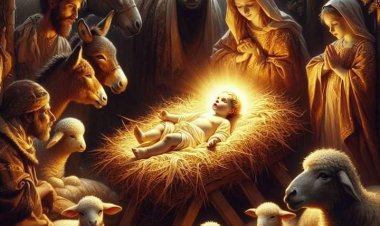

The doctrine of the resurrection of the body underscores the importance it attaches to the body. “The mark of the Christian is the willingness to look for the Divine in the flesh of a babe in a crib, the continuing Christ under the appearance of bread on the altar, and a mediation and prayer on a string of beads” wrote Bishop Fulton Sheen.

Aquinas dealt with the question of why Christ did not commit any of his teachings to the written word. Aquinas’ answer is valid at all times. He states that it was in keeping with Christ’s excellence as a teacher to teach in the most excellent manner possible. This manner consists in imprinting His doctrines on the hearts of his hearers (S.T. III, 42, 4). Christ, like Socrates before Him, taught as a person which is to say, bodily, tangibly, communally. He was, as Gabriel Marcel would say, present to His disciples. He would not have allowed Himself to be trapped in the net or diffused throughout cyberspace. We might ask the question, “If Christ entered the contemporary world, would He have His own website or communicate to others through the World Wide Web?”

The Catholic Church has ceaseless praise for the incarnate reality of motherhood.

Mary, the Mother of God, saves us from an abstract Christ, a God who is forever incorporeal and intangible.

A person is a flesh and blood, body and soul entity.

How do we deal with the World Wide Web without becoming de-bodified and depersonalized?

The computer, of course, is a tool to serve people, not a place to live.

It is inevitable that people overestimate the significance of their creations.

We should not turn our inventions into idols.

When shopping malls became fashionable, it became trendy to get married in them.

Now some couples have started a trend to get “married” in cyberspace, online via their computers.

The web does bear interesting analogies with two worlds that are very much part of Catholic teaching, namely, the Mystical Body of Christ and the Communion of Saints. These worlds are unified, not electronically, but by love, prayer, and grace. These three factors act as a kind of “electricity of the heart.”

We are communal beings, and in Covid pandemic times the www has helped maintain communication, but we should not be content with a community that requires the exclusion of our body.

The web demonstrates, in a spectacular way, how limitless pieces of information can be brought together from far-flung places at the speed of light.

Still this is only a small step toward the kind of interpersonal community that is embodied in the Mystical Body of Christ and the Communion of Saints.

And living mainly on the web presents the danger of depersonalization. It is merely a foretaste of something far better.

Perhaps the best use of the World Wide Web is to make both the Mystical Body of Christ and the Communion of Saints more believable. But it must not tempt us to de-emphasize the indispensable importance of the many “communities of persons” needed in order to remain whole and fully real: friendship, marriage, the family, the neighbourhood, the parish, and the nation.

- Adapted from DONALD DEMARCO